Let’s begin by agreeing that when assessing the “rate” on any instrument, we must remember that rates are a summation of expected returns on risk-free instruments, plus adjustments for the risks and costs associated with the different asset classes. Credit card loans carry a higher rate presumably due to larger losses on credit extensions. Mortgage loans have very low historical default rates, but given the fixed-rate and longer-term characteristics, they require a return to compensate for the time-value of money. Different investments carry higher or lower yields depending on when the cash flow is returned to the buyer, the certainty of the cash flow return, and potential losses in the underlying collateral that may pass along to the bond holder. Using this concept of risk-adjusted pricing helps in today’s times to find answers to the question of where to place liquidity so that it enhances profitability.

Rest assured, though, the same process we use today to deal with extra liquidity on hand is the exact same approach we take when liquidity is not as plentiful. In those cases, our decision rules might be modified, but the fundamentals of the process do not change.

The following section lays out a decision-making process that should be reviewed regularly and adapted as market conditions change, as they always do!

First, answer this question: Are we trying to decide what to do with the money you already have on the books, or are we trying to find ways to grow the balance sheet and going to need new funds as a result?

Let’s say we are considering a new commercial loan and our competitor is offering a 5-year fully amortizing loan at 2.50%. Sounds crazy, right? Consider that on the day we were considering a 5-year loan at 2.50%, you could borrow money in the wholesale market for 0.57% for 5 years (for a “bullet” advance; an amortizing advance rate is 0.37%). So, assuming you had to “buy” money from a wholesale source to fund the loan, you would have a spread of 2.13% (2.50% – 0.37%) which isn’t great compared to your traditional margin. Of course, there are many funding options to consider, but the issue is how much incremental spread do we add.

On the other hand, if what we really have is a situation where we already have the money (like many financial institutions do right now), we are paying an average cost of funds of 0.65%. In that case, the issue here is that we are investing 0.65% money today in a “cash” account at 0.05%, so we are losing 0.60% on the funds. When we add the 0.60% lost value back to the loan returns, things get a little brighter!

See, if we already have the money on the books to invest, the only real question is where can we invest the funds where we understand the risks and costs we are taking and know we are being compensated for the risks. Notice I have not yet said whether the load rate of 2.50% is a good rate for that kind of credit. We will get there, but I am simply pointing out that for every $1 of funding that we could put into a higher returning asset that is currently “losing” money relative to what we are paying for it, we must seriously look at the option of doing so.

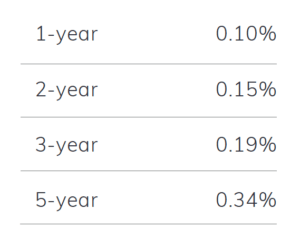

When we look at the 2.50% 5-year loan and we compare what options we could invest in today in a “risk-free” investment, we see the following rates for Treasury investments:

Just eyeballing these rates, we might be able to earn a total rate of 0.25% in a risk-free investment of the same cash flow life as our loan. Agency bonds which are more common in community FIs might offer us an additional 10-15 basis points and are also essentially “risk free.”

So, let’s assume a 0.35% risk-free return is possible for a 5-year amortizing set of cash flows. Now we add in the risks and costs of the loan as well as any fees. Let’s assume no fees for simplicity here. But we probably have some origination expenses to incur making the loan. There are ongoing servicing costs we would have if we made the loan vs. not making the loan. There is the potential credit risk that the borrower may not pay us back. At the end of it all, if the sum of the costs is more than the difference between the rate and the risk-free investment, then don’t make the loan. In our example above, 2.50% - 0.35% = 2.15% is the spread available to cover risk and cost.

Note that risk decisioning on the balance sheet comes into play here. If you are considering moving into an asset that has a much longer duration and you are already heavily concentrated in long-duration assets, then making a further bet may not be the best idea in total, even though the individual “loan spreads” may make sense. In that case, maybe you can make and sell the loans. Sounds like many 1-4 family mortgage portfolios today. That is an overall asset/liability management decision that requires more time and attention, so stay tuned for that.